Our History

A rich heritage in the billiards business since 1850

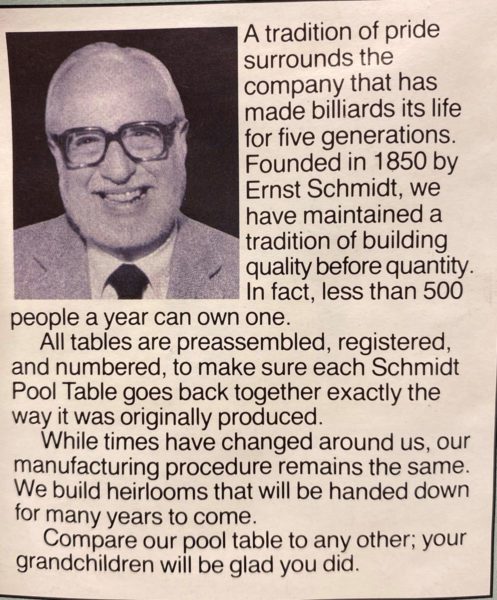

A.E. Schmidt is not about buildings, factories, or storefronts that we have occupied, it’s about people! Our rich history began with quality craftsmanship and remains our standard for all manufacturing, sales, and services. Since 1850, we have created some of the most beautiful and solidly built pool tables ever made.

Who were the people who built a company strong enough to last 170 plus years from nothing? What were they like and what did they do to make their mark? Check out the interesting history behind the A.E. Schmidt Billiard Co. and the legendary quality craftsmanship behind each of our beautiful pool tables and game room furniture.

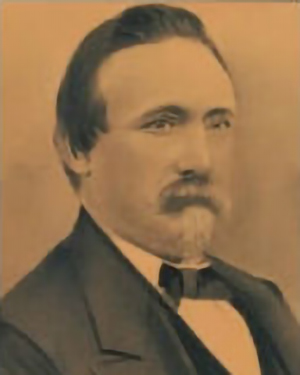

Ernst Schmidt, the founder of A.E. Schmidt Co., was born October 28, 1823 in Celle (pronounced “Zelle”) Germany and christened Heinrich Ernst Friedrich Schmidt in the Celle Evangelical-Lutheran Church.

From church, census, and military records we learn that Ernst’s father, Otto Friedrich Ernst Schmidt, was born in Hannover State on July 12, 1792, married Sarah Hoadley on January 29, 1817, and this couple had three children: a daughter Auguste, and two sons Georg and Ernst. Otto apparently was a Master Carpenter, because on December 7, 18l7 he was “hired” by the Hannover State Military Company and ranked as a corporal. He qualified for a Second Lieutenant’s pension when he received his discharge on October 8, 1819.

No records were found that either Georg or Ernst had served in the military, and as the year 1850 approached both would soon have to report for their compulsory military training. This, coupled with Otto’s death, possibly spurred the family to emigrate to the United States.

From letters penned to and from Ernst, we learned that Otto and Sarah had been divorced, Otto had remarried, and that when he died his estate passed to his and Sarah’s children.

No information was uncovered as to exactly when and how the family left Germany and traveled to St. Louis, but we do know that Ernst, Georg, Auguste and their mother Sarah were in St. Louis in 1849 and Auguste was married on January 27, 1850 to Johann Lehman, a Belleville, Illinois painter. In a letter mailed from St. Louis on September 12, 1850, Ernst thanked Johann for the “nice shelter I found with you”.

A letter mailed to Ernst on October 6, 1850 from Hannover by his uncle, Friedrich Schmidt, Merchant, indicates that Ernst had inherited Ono’s house, the house had recently been sold by Ernst’s attorney, and the sale proceeds would be sent to Ernst.

Ernst had arrived at an unusual time in St. Louis, and had to delay for a year establishing his business. In 1849 gold had been discovered in California, and St. Louis, the largest city of the West; was a jumping off place for the 49’ers. The city was crowded with prospectors outfitting themselves for the long trek to the West Coast, when “The Great Levee Fire” broke out on May 19th, destroying 20 steamboats and 8 entire blocks of business buildings.

Ernst found instant employment. He was a competent cabinet-maker, as well as a Master Turner, and the demand for these skills kept him busy until late 1850. The delayed opening of his shop was a blessing in several ways: he was able to add considerably to his legacy; he learned to speak and write French — the prevalent St. Louis business language — and he had time to find just the right location for his business.

In the Fall of 1850 he put his “shingle” in the window of a strategically located building 50 feet Northwest of the St. Louis Cathedral. The shingle read:

ERNST SCHMIDT

TURNER AND DEALER IN IVORY

BILLIARD BALLS, TEN PIN BALLS, AND SMOKING PIPES

CONSTANTLY ON HAND

JOBBING WORK AND REPAIRS OF ALL KINDS DONE WITH NEATNESS AND DISPATCH

12 SOUTH THIRD STREET

BETWEEN MARKET AND WALNUT STREETS

Three blocks to the north, at Third and Olive Streets, was the “new” Post Office. Three blocks to the east was the loading dock of the steam ferry-boat, The St. Clair, which carried passengers and vehicles across the Mississippi to Illinois. And at the comer of Third and Market was the starting point of the Omnibus.There were no trolley cars at that time, and the only public transportation was by horse-drawn taxi-cabs or the Omnibus — a long, flat bed wagon with benches attached, seating about 20 people and drawn by 2 horses — fare 5 cents. The bus started about 100 feet from Ernst’s shop, traveled West two blocks to Broadway, then North to the end of Broadway, then turned around and went back to Third and Market.

Business success is frequently the result of “being in the right place at the right time”, and having the right products for your market. Customers could easily reach Ernst’s shop from almost anywhere in the city — which at that time was mostly concentrated North and South along the river and Broadway: and passengers could walk in a few minutes from their steamboats along the levee to Schmidt’s place.

The Thurston Company in Great Britain had in 1826 replaced the wood playing surfaces (beds) of billiard tables with slate; and in 1840 began to use molded gum rubber as rail bumpers or cushions in place of canvas sleeves stuffed with cotton, rags, or felt. These improvements, copied by American table-makers, sparked the greatest percentage increase ever experienced in billiard table manufacturing.

In Cincinnati, J. M. Brunswick, who had been making carriages there since 1840, in 1845 started building vastly improved billiard tables with slate beds and rubber cushions. He soon had to expand his shop to a factory, then to factories, and in 1848 established a sales office in Chicago, followed by one in New Orleans in 1852, then in 1859 a sales office and billiard room in St. Louis.

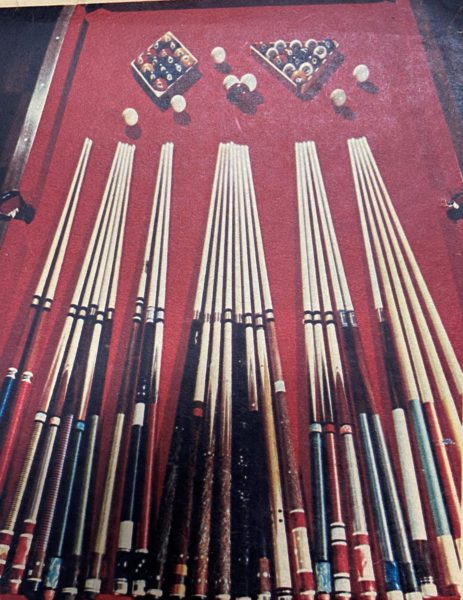

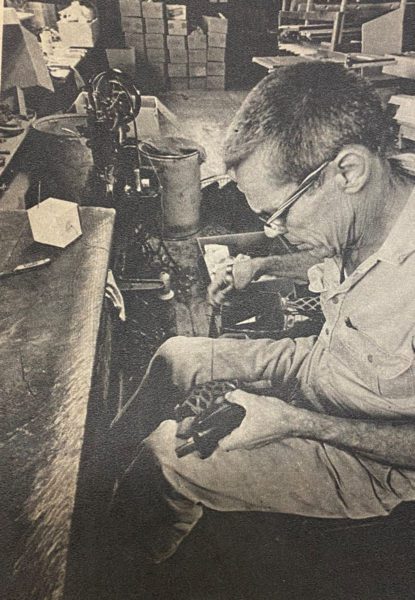

In addition to manufacturing ivory and Boxwood billiard balls, Lignum Vitae ten pin balls, and smoking pipes, Ernst had a thriving trade in “Jobbing Work and Repairs of All Kinds”. The balls had to be trued and re-colored every few years; cues needed new ivory or buckhorn ferrules and leather tips attached; tables had to be moved and re-covered or have the new style rubber cushions attached.

Other repairs included making ivory or staghorn cane heads and umbrella handles; ivory or bone dice; pistol grips and gun butt inlays; and furnishing jewelers with turned ivory products. For his buckhorn ferrules, dice, cane heads, umbrella handles and pistol grips, Ernst purchased stag antlers in large quantities; occasionally shipping car-loads of trophy antlers to Europe for hunting lodge wall decorations.

Ernst’s business prospered and grew with the City of St. Louis. From 1850 to 1860 population increased from 74,439 to 160,773, and St. Louis became the third largest city in the United States.

By 1853, Ernst, now 30 years of age, felt financially secure and capable of supporting a family. On March 5 of that year he married Caroline Grimminger, another German immigrant. Unfortunately, Caroline died in 1855, without having had children. Family-wise, this was a rough time for Ernst — his sister Auguste Schmidt Lehman passed on in Belleville in 1856. On October 27, 1858, Ernst married Caroline’s older sister Elizabeth (called Elise) Grimminger, who had lost her husband in late 1856, and Ernst adopted her one-year old daughter, Sophia Siemers. Ernst’s and Elise’s first child Oscar Wilhelm, was born November 26, 1861, followed by Augusta (1863) and Pauline (1865).

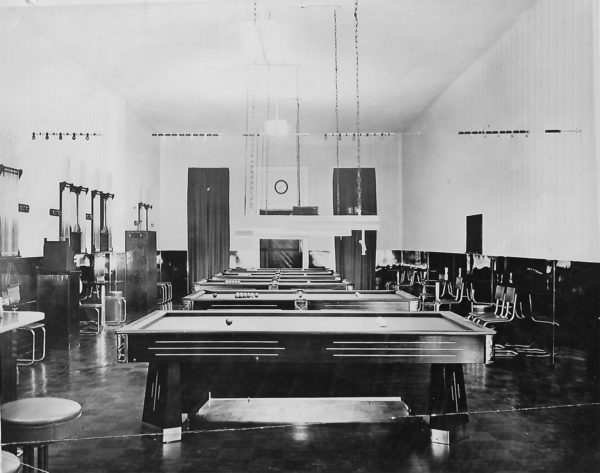

From 1860 to 1865 — the Civil War years — most St. Louis businesses suffered stagnation or losses. But Ernst’s trade continued to grow because of the ever increasing popularity of bowling and billiards. Travel by rail and river greatly increased, and in large and small cities, hotels and saloons were installing billiard tables or bowling lanes, or both, to entertain their guests. For instance, in 1862 work commenced on St. Louis’ largest hotel — The Southern — occupying the block surrounded by Walnut, Fourth, Fifth and Elm Streets — just four blocks from Ernst’s shop. The Southern opened in 1866 and featured a magnificent billiard room furnished with 15 Brunswick “Monarch” pocket and carom billiard tables.

Then in 1869 the second greatest boost for billiard play was introduced — pocket billiard balls which looked and played Like ivory, but cost only one-tenth as much as ivory. The balls were made of “Celluloid”, the world’s first plastic, created by compressing nitro-cellulose and camphor — an invention of John Wesley Hyatt and his brother, Isaiah, of Newark, N.J.

The late 1860’s were fun years for Oscar. Like successive generations of Schmidt children, when he passed his fifth birthday he went with his Dad to the shop on Saturdays, learned to use simple wood working and machine tools, and took part in the Saturday afternoon shop and store clean-up. By the end of the decade, now nine years old, he could operate the steam-powered lathe and produce wooden pegs and dowels, turn wooden balls, and repair cues. In the early years of the 1870’s he continued to work part time and by the time of his graduation from public school he was a proficient ivory turner. Then, in his “jumping out of the nest” years, he worked at various wood-working plants: one a furniture factory in Kansas City, and in 1879 at the Julius Balke, Thonssen, and Pfirrmann Billiard Tables and Frame Factory at Sidney and Main Streets, St. Louis.

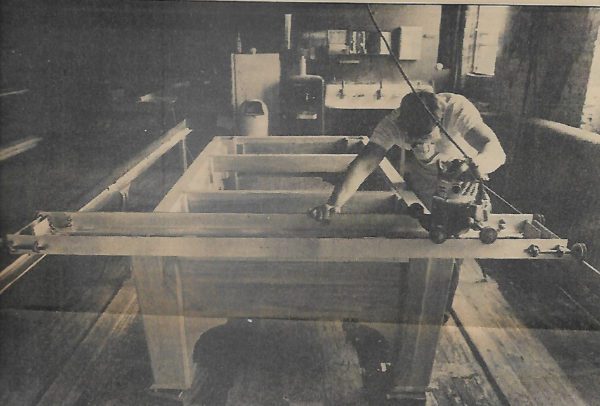

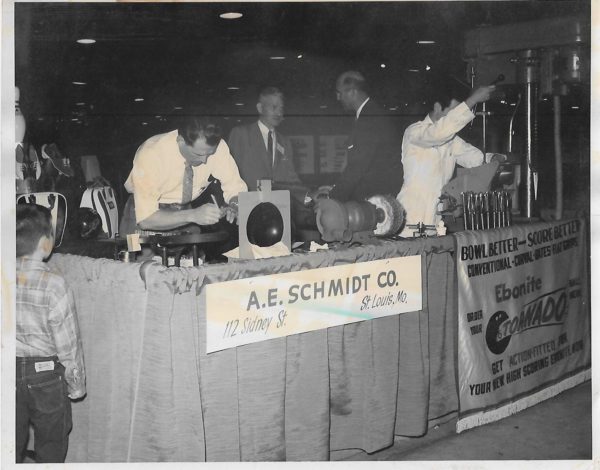

In this building, now numbered 112 Sidney Street, Oscar Schmidt learned to build pool tables. A.E. Schmidt Co. records show that in 1880 Oscar became a partner with his father, Ernst, and immediately expanded the billiard inventory from just balls and cloth to a complete line of supplies. In 1882 he built his first pocket billiard table at 12 South Third Street.

In 1883 the Schmidt partners moved to a larger location at 328 Market Street, just around the corner from 12 South Third Street, to gain space for constructing pool tables.

“Pictorial St. Louis 1875” shows 33 breweries and Malt houses. By 1880, with a population of more than half a million, St. Louis was reported to have more than fifty brewers and a thousand saloons. At that period, beer wasn’t bottled or canned, it was drawn directly from the keg, just as “Draft” beer is today. Most saloons carried only one brand of beer, and there was intense competition between the brewers to have their brand in a bar. Occasionally, a brewer bribed a saloonkeeper to switch to his brand by offering to let the bar room use one of the brewer’s pool tables. For exceptionally good locations, breweries were known to furnish bars and back-bars, booths, and tables and chairs as well as pool tables. This led to a search by the breweries for less expensive tables than the veneered and inlaid beauties the Brunswick, Balke, Collender Co. was selling, and they found that the inexpensive and substantial, plain Jane, solid wood frame Schmidt tables answered their need.

In addition to selling and installing new tables, Ernst and Oscar now had a brisk business of moving tables in and out of breweries and bars, and furnishing necessary repairs and supplies, and another “niche” business — “trade checks”. The checks were brass, coin-sized tokens stamped with the bar name on one side and the words “Good for 5 cents (or 10 cents) in Trade” on the opposite side. To make the table games more interesting, the loser had to pay the bar 5 cents or 10 cents per game, and the winner received a 5 cents or 10 cents merchandise token from the house. Although this added spice to the game, and for a while sparked table sales, it eventually made “pool players” and “pool rooms” notorious names. Some of the better players practically lived and worked in the bars — eating, drinking and playing at the inexperienced players’ expense. The era of the “pool hustler” was born.

At the same time that billiard table manufacturing was increasing, small cities were springing up around St. Louis. In 1874 the Eads Bridge across the Mississippi River was completed to carry rail and vehicular traffic and St. Louis became a railroad center as well as a steamboat center. The Schmidt name became synonymous with billiard tables and supplies throughout Missouri and Illinois. The company prospered.

In 1882, Wilhelmina Grimminger Kliefoth, Ernst’s sister-in-law, gave birth to a son, Adolph. Adolph’s cousin Oscar Schmidt, now 21 years o1d, was asked to be his god-father. Oscar took this nomination seriously, and in later years it was said that Oscar had adopted Adolph. In all ways, Adolph Kliefoth was treated as a Schmidt family member. He was a full partner in their partnership, and in 1920 an incorporator and first President of A.E. Schmidt Company.

October 10, 1888 Oscar married Anna Elizabeth Zelch. They had three children: Edwin Heinrich born 1891; Ernst Johann in 1894; and Irene, 1898.

Heinrich Friedrich Ernst Schmidt passed away peacefully in 1895 — secure in knowing that he had established a business that would support his family.

By 1898, Dolph Kliefoth, now 16 years old and already a trained cabinet maker and turner, was working full time for Oscar, and helping to show Edwin, age 7, the “ropes”.

Oscar is credited by the family for keeping its business on a sound financial basis, and afloat during tough times. He was a disciple of the “toil, sacrifice, saving and abstinence” culture of his forefathers, putting surplus funds into interest-bearing securities and rental real estate, and always having enough cash on hand to pay his employees and suppliers. Time payment terms were not for him. His motto was “if you can’t pay for it, don’t buy it”. (During the Great Depression of the 1930’s he told his sons and Dolph, who at that time were the active managers of the Company: “Don’t worry. Money will be tight, but we can weather any storm. I’ve been through many tight times, and the company that can hold on will be stronger when the storm has passed”.) Oscar furnished cash as needed, the Schmidt Company survived numerous recessions but many of their competitors didn’t, and the Schmidts picked up new customers as the company celebrated its 50th Anniversary in the year 1900.

By the end of the 19th Century, the Industrial Revolution was passing from the Age of Steam Power into the Century of Electric Power and the Age of Technology. St. Louis had been “electrified” in the 1890’s with electric motors replacing steam engines in factories, electric-powered street-cars replacing horse drawn rail trolleys. Cross-country railroads made the city the transportation center of the nation. From around the world citizens and foreigners came to “Meet me in St. Louis, Louie” at the World’s Fair of 1904, to enjoy this City of Lights and marvel at the beautiful thoroughfares, parks, and buildings of this great metropolis.

Automobiles and airplanes were in their infancy. Moving picture theatres and phonograph players were becoming popular forms of amusement, but, Billiards and Bowling were still the leading indoor entertainments. The book BRUNSWICK: The Story of An American Company notes that “By the end of the 1910’s Brunswick was selling tables as fast as they could be produced at its eight factories in the East and Midwest” … and “by the 1920’s there were more than 42,000 pool rooms in the United States — 4,000 in New York” … “In 1895 the American Bowling Congress was formed and immediately established specifications for the sizes of lanes, pins and balls, and a uniform method of scoring. In 1906 Brunswick introduced a hard rubber bowling ball that made the old Lignum-Vitae balls obsolete”.

Into this volatile scene, the third generation of Schmidts — Edwin and Ernest — entered to put their enduring marks on the Company. In their teen years, they worked with Oscar and Dolph in the shop and as repair and installation mechanics. One of their favorite stories was of delivering pool tables on street cars. (Oscar was teaching them to work in the most economical way.) Although it took 3 trips for the two boys, the trolley transportation fare of 5 cents per person for each of the 3 trips totaled only 60 cents — several dollars less than renting a team of horses and a wagon at the nearest livery station. The back platforms of the trolley cars were not under cover and had no seats. On the first trip Ernie would stand on the platform and stack the disassembled table parts and supplies as Ed passed them to him. On the next trip, two of the 4 slabs of slate, weighing about 150 pounds each, which they had stacked against an electric light pole, were slid onto the platform. They rode to their stop, unloaded the slates and carried them to the saloon where the table was being installed, then returned on the next available car to repeat the operation. Oscar paid them each $1.00 per day, the current rate for labor, and bought their lunch. So, for less than five dollars they delivered and installed a pool table at any bar located on the Market Street – Broadway trolley line.

The low pay and hard work probably inspired them to seek other employment. Ernie, having discovered that he had inherited Ernst’s and Oscar’s woodworking and mechanical skills went to work part time at Essmueller Mill Furnishing Company where his uncle, August Berblinger, was installation superintendent. In this way, he learned to be a millwright while attending Central High School. In 1913 he enrolled at Missouri University at Columbia, MO., and was a student there until he enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1917. Because of his mechanical skills he was assigned to an Army Air Force Base at Fort Myers, Florida as an airplane mechanic. World War I was the first conflict to see aircraft used as observers, spotters and fighters. Mechanics were an important part of the flight crew — they did not fly missions, but after they had completed body and engine repairs, they were required to go on test flights, sitting in the front cockpit to be certain that no further remedial work was necessary. Ernie survived all these flights, including a crash landing, never went overseas, but continued as a mechanic until the war ended November 11, 1918.

When Ernie returned to civilian life in 1919, he opened his own small business on Folsom Avenue — The Jiffy Tip Company where he manufactured tips and ferrules for A.E. Schmidt Co. In 1921, his shop was destroyed by fire, and Ernie joined Oscar, Dolph and Ed as superintendent of their factory.

Ed went his own way. He quit school after the seventh grade and went to work as a clerk in Nugent’s Dry Good Store at Fourth and Washington Streets. Finding that he liked selling, he moved into a larger field — Real Estate. He was still single and living with his parents, and by 1910 Oscar convinced him that he could have just as much fun selling billiard equipment. They struck a deal: Ed could take over the sales and general management of the Company while Oscar and Dolph ran the shop and factory. Within a year, table sales increased to the point where they needed more factory space, and the Company moved to a three-story building at 1111 Pine Street.

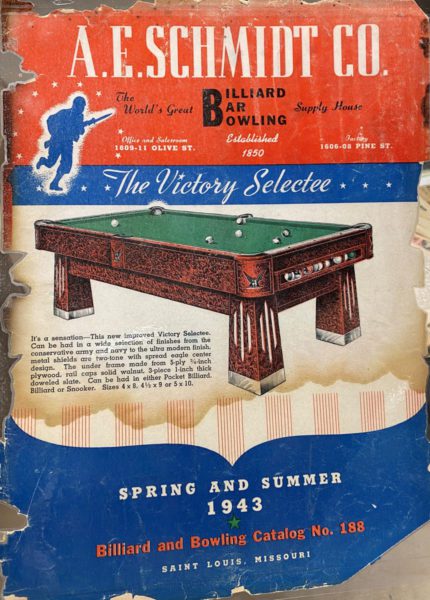

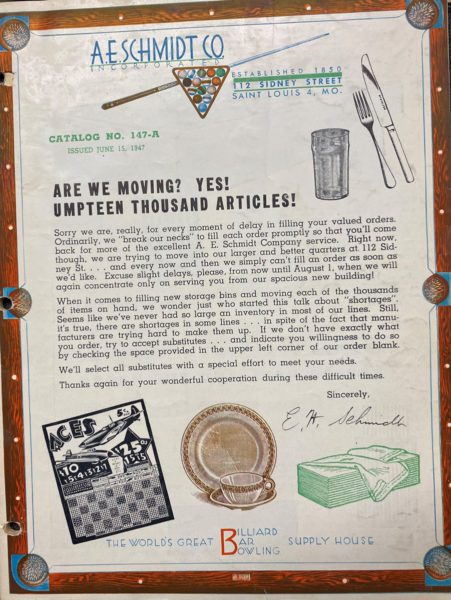

Ed, realizing his need to know more about business methods, enrolled in a correspondence course with the Harvard School of Business, which he completed in his spare time over a period of several years. He studied Direct Mail Advertising and saw that Sears Roebucks’ format could be applied to his business. His partners agreeing, in 1911 they produced an 8-page illustrated catalog with prices 20% to 25% less than Brunswick’s, and mailed it to customers and prospects in Missouri and Illinois. Orders received in the morning mail were shipped the same day. Customers liked the lower prices and prompt shipment, and over the next half century, Direct Mail grew to be the Company’s principal form of advertising.

As mentioned, the 1910’s were busy times for billiard table manufacturers. The Schmidts couldn’t produce all the tables they could sell, and purchased additional tables from other manufacturers — principally Missouri Billiard Manufacturing Co. and the Wendt Mfg. Co. of Milwaukee. They purchased the vacant lot next door at 1113 Pine Street, built a larger 3-story building with full basement, and moved their office and shop in 1920.

Also in 1920, they incorporated the business as A.E. Schmidt Co. (named for Anna Elizabeth Schmidt, Oscar’s wife). The first officers were Adolph Kliefoth, president; Oscar Schmidt, vice president; Edwin Schmidt, secretary-treasurer.

That same year, the Company’s substantial business of supplying and maintaining pool tables owned by the breweries and installed in saloons crashed. On October 19, 1919 the Volstead Act, prohibiting the manufacturing and sale of alcoholic beverages, became law as the 18th Amendment to the United States Constitution. Almost all of the St. Louis saloons closed their doors in 1920, as did most of the breweries. A few brewers continued, bottling non-alcoholic “soda-pop”, root beer, sarsaparilla, and “Bevo” by Anheuser-Busch. Outside of the metropolitan areas, the saloon-keepers took down their “Bar” signs and became “Pool Rooms”, selling “soft” drinks, sandwiches, and recreation.

Seeing this radical change in his market, Ed changed tactics. He hired salesmen to personally visit billiard and pool rooms in Missouri and Illinois. He expanded the catalog mailings to eight states. Thousands of used bar pool tables flooded the local market during 1920 and 1921, the Schmidt Company buying as many as they could sell and warehouse. The new corporation weathered the storm: Missouri Billiards didn’t, that company folded in 1923.

Fortunately, Ed had not been drafted into military service in 1917. In 1914 Ed married Hilda Bertha Berlinger, a distant Grimminger family cousin, and this couple had two sons: Harold born in 1916 and Arthur in 1917 — and was draft-exempt. (A third son, Edwin H. Schmidt Jr. was born in 1923.) Dolph, because he had a young son, Richard, was also draft exempt. As mentioned previously, Ernest joined the family business in 1921 and immediately assumed management of the factory. Now, in addition to making as many tables as possible, and buying more from Wendt, they were reconditioning and selling bar tables and getting mail orders for supplies from a substantial number of the Nation’s 42,000 pool rooms.

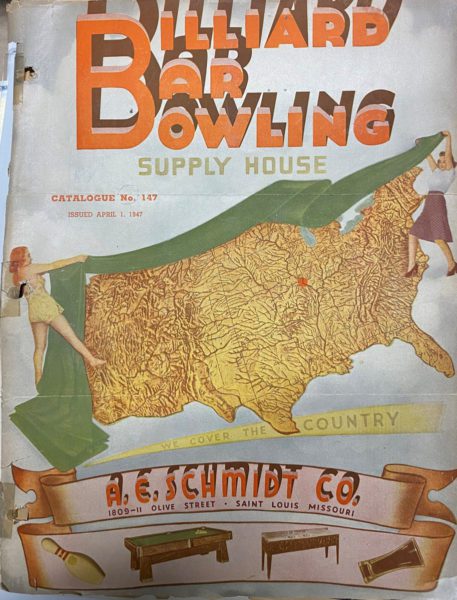

Business was booming. Looking to the future, in September, 1925 AESCO (the acronym for A.E. Schmidt Co.) purchased two large building lots at 1809-11 Olive Street and started construction of a factory building. But, before the building would be occupied by AESCO, several more storms had to be weathered.

Almost unnoticed, Billiards and Bowling were losing their “lock” on the entertainment field. Automobiles and new roads which were helping salesmen to make their rounds, were moving pool players, too, not to pool rooms but to movies, dance halls, roller rinks, and professional sports playing fields.

The “pool hustler” image which started in the bars grew faster in the saloons which had been converted to pool rooms after 1918. Movements to outlaw pool rooms were carried to State Legislatures. If the rooms weren’t out-lawed, then a lesser but just as devastating weight was put on them: “Minors not permitted to Play”. Churches picked up a new devil to exorcise. The billiard boom of the early 1920’s suddenly collapsed.

But, a new boom — RADIO — had started, and Ed thought that sales of radio sets and parts might replace lost sales of pool tables and supplies. A building on North Kingshighway, by now the center of St. Louis City and County population, was rented for a salesroom. Part of the traveling sales team was pulled off the “road” to staff the satellite store. Sales were brisk for several years, but collapsed as the Great Depression took hold. The Kingshighway store closed in February, 1930.

In April, 1926 Oscar, Ed, Ernie and Dolph had formed a real estate partnership — AESKO (acronym for A.E. Schmidt and Kliefoth) Realty Co. — and purchased all of A.E. Schmidt Company’s buildings. No longer needing additional factory space, in 1927 the new building at 1809-11 Olive Street was rented to the Armstrong Furniture Company: that company succumbed to the Depression in 1929.

The Depression deepened. Operators who had purchased tables from Schmidt on an installment payment plan couldn’t make their payments, which were 100% financed by A.E. Schmidt Co. Giving them the same advice that his Dad had given him, Ed told his debtors “If you can stick it out through these tough times, we will allow you to pay just the monthly interest on your debt to us; and when business picks up, as it will, you can make payments on principal”.

Some did, some didn’t. Those who did became loyal friends and the Company’s best boosters; those who didn’t were forgiven their debts when their mortgaged tables were returned to or picked up by the Company.

Now the building at 1809-11 Olive Street, which had been envisioned as a factory, was needed to help warehouse the hundreds of tables which had been re-possessed. In mid-1930, the office and salesroom were moved from Pine Street to the first floor on Olive Street, the repair shop and factory to the second floor, and the basement was used for storage. Tables were also stored in the basement and on the second and third floors of 1113 Pine Street, and the first floor continued as a radio and parts, billiard tables and supplies sales store. In January, 1933 Ed’s oldest son, Harold, graduated from High School and was installed as manager of the Pine Street Store at a salary of $3.00 per week.

The Depression steadily worsened from 1929 to 1933. The low point was marked by the closing of all banks shortly after President Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in February, 1933. Businesses of all kinds either closed completely, or continued selling for cash or credit … with no banks operating, checks were worthless. AESCO banked at the 18th Street National Bank across the street on the southwest corner of 18th and Olive Streets. This bank went into bankruptcy — never reopened — and only a small percentage of Schmidt’s deposits was recovered at the end of bankruptcy proceedings five years later. During the period of the Bank Closings, State and Federal bank examiners were working overtime looking at bank books and records to see which banks would be allowed to reopen. In about one week, enough were opened so that business could resume. Again, thanks to Oscar, who lent AESCO enough cash to establish a new account at Mercantile-Commerce at 8th and Olive Streets and start climbing out of the hole. The Great Depression was a Tough Teacher, and those who went through it never forgot its lessons.

Thanks, too, to Franklin Roosevelt for using the credit and resources of the Federal government to re-start the wheels of business. Two of his programs greatly helped AESCO. The Civilian Conservation Corps. (CCC), with Army brass as superintendents, opened camps all over the United States. Young men were enlisted at a very minimum wage, fed and housed, and worked improving parks and public recreation areas. The boys needed amusement in their off hours, and what better entertainment is there than a pool table? When mail orders from CCC camps began to come to Schmidt from areas where catalogs had been mailed to pool rooms, Ed saw a fresh new group of customers. From the U.S. Department of Commerce he obtained the addresses of all the camps, and sent them brochures and catalogs. Soon the camps were purchasing tables as well as repair parts and supplies. At the same time, Ed purchased new mailing lists of pool rooms and sent his mailings nationwide.

A minor miracle occurred. Orders for billiard supplies came to Schmidt from all over the country. Why? As the book BRUNSWICK: The Story of An American Company tells it: “Though the thousands of pool parlours around the country were experiencing a boom, thanks to the tens of thousands of idle workers who found the rooms fine places to spend their time, the sales of new tables were virtually non-existent … Company sales had fallen to a low of $3.9 million in 1932 from $29.5 million in 1928. During the early 1930’s, the company’s losses averaged $1 million a year”.

Brunswick and A.E. Schmidt Co. were among the handful of billiard manufacturers and suppliers to survive this disastrous depression. Oscar’s prediction was coming true.

The second Roosevelt initiative — which had an even greater effect on A.E. Schmidt Co. — was the revocation in 1934 of the Volstead Act. Those brewers who had switched to non-alcoholic beverages started brewing beer again, and other breweries re-opened. Breweries, under new Federal regulations, were prohibited from furnishing pool tables or any other fixtures to the newly re-opened “Bars” or “Taverns” (the regulations forbade the name “Saloon”). In St. Louis, a local ordinance prohibited pool tables in taverns or alcoholic beverages in pool rooms.

Despite these new restrictions, Ed saw an opportunity to sell bar supplies, beer drafting equipment, furniture and glassware to the newly re-opened bars. Outside of St. Louis, many pool rooms applied for permits to sell beer and wine. Ed sent them the company’s “Billiard, Bowling, and Bar Supplies and Equipment” catalog, and, again, mail orders increased. In many rural communities, new billiard parlours and taverns were opened. Schmidt’s stock of re-possessed tables shrank, making warehouse space for tavern supplies. The taverns added small kitchens; Ed added restaurant supplies to his inventory.

In 1934, the Company decided to get out of the Radio business, and the inventory was auctioned off. The Pine Street sales office was closed and the entire building was now used as a warehouse. Harold moved to 1809-11 Olive Street and took over all of the bookkeeping and some of the store sales. Justin FelDotto, who had been the Company’s traveling representative in Illinois and Indiana until he was laid off in 1932, was called back to work. Robert Schwerdtmann, whose family for many years had a retail and wholesale toy distributing company in downtown St. Louis, asked Ed for a job after Schwerdtman Toy fell victim to the Depression. He was immediately employed as sales rep for Western Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Iowa.

In 1935, Arthur Schmidt, Harold’s brother, graduated from High School and joined his family at AESCO, gradually taking over Harold’s job of bookkeeping and sales at 1809 Olive. Harold became the Company’s representative in Eastern Missouri, Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

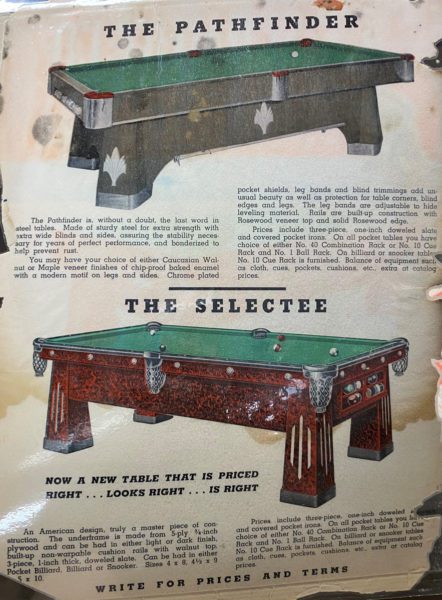

Brunswick-Balke-Collender Co., still the acknowledged leader in billiard table design and construction, in 1935 introduced its “20th Century” line of Art-Deco tables. The 1925 series of tables, which featured heavy wooden frames with dark veneers and inlays, was supplanted by tables with lighter weight plywood frames, deep aprons under the rails and metal shields concealing the leather pockets. Billiard room proprietors welcomed the new styling, but hesitated to trade in their heavy tables for lighter models.

At that time there were fewer than ten table manufacturers in the nation, and all of them — including Schmidt — “Followed the Leader” and redesigned their products. AESCO introduced another option — why not “streamline” the older, heavy tables to give them the Art-Deco look? Ernie designed a chrome-plated shield with a triangle design, built sample sections of table corners with the deep panels and chrome shields for the salesmen to show their customers, and “streamlining” orders streamed into the factory.

Unexpectedly, in 1936 our good friends and loyal opposition at the Brunswick, Balke, Collender Company handed A.E. Schmidt and other regional billiard suppliers a lovely present: a national network of local billiard dealers. Brunswick, with headquarters in Chicago, factory in Muskegon, Michigan, branches and warehouses in six major U.S. cities, about 50 sub-dealers in smaller cities, changed its sales policy. Brunswick would no longer sell tables and supplies through the dealer network — henceforth all sales would be handled by company representatives working out of Chicago and the six branches. The stunned dealers started looking for new sources of tables and supplies. Ed and Ernie seized the opportunity, worked up a wholesale price list for dealers, and sent their sales reps back into the territories to seek out and convert former competitors into present customers. Price lists were mailed to all former Brunswick dealers not contacted by AESCO, and new accounts were established as far distant as California, Florida, and Georgia. Most of the Midwestern dealers became loyal Schmidt accounts. Harold established enduring friendships with Calvin Jones, Jones Bros. Distributing Co. in Little Rock; John Turcott, Rex Billiards in Memphis; and Red Stoker in Fort Worth.

Increased sales meant increased purchases of supplies, and larger purchases earned lower prices. Soon A.E. Schmidt Co. was getting the maximum discounts given by manufacturers, enabling Schmidt to further discount its prices and more orders came in from all over the country. The Sears-Roebuck system was working for Ed and Ernie!

In 1937, AESCO bought a building at 1608-10 Pine Street to use as a factory. The cue and ball repair shop remained on the second floor of 1809 Olive, and the space vacated by the factory was used to house the expanding inventory. The billiard supply catalog of 8 pages had now grown to 24 pages of Billiard, Bar and Bowling Supplies and was being mailed to customers and prospects in 48 states.

The new factory continued to manufacture solid oak and mahogany tables, now with the streamlined Art-Deco look, and, as a price leader, a plywood frame table with painted mottled red and black legs and side panels. Even with the additional space, the factory couldn’t keep up with the demand. Ernie and Ed, looking for ways to increase table production, hit upon a plan to have a local metal processing plant fabricate sheet steel table legs, sides and rail panels, finished with a baked enamel wood grain design. At the Schmidt factory a thick poplar slate support frame was attached to the legs and sides, Schmidt rails with walnut or rosewood tops and newly designed “Eagle” chrome pocket shields were fitted to the slate — and table production was doubled.

In 1939, Harold proposed to his Dad and Uncle that A.E. Schmidt Company open a branch store in New Orleans which he would manage and serve Company customers in Louisiana, lower Mississippi, and East Texas, where there were no billiard suppliers other than Brunswick’s branch in New Orleans. After a few days consideration, the answer came that the Company didn’t want branches, but if Harold wanted to invest his own money, the Company would give him an exclusive dealership in that area.

Leonard FelDotto, Justin’s youngest brother, worked in AESCO’s shop and factory and had been trained to repair cues, install and repair tables. In the Fall of 1939, Len and Harold went to New Orleans and opened Schmidt Billiard Supply Co. at 628 Carondelet Street. The business was successful: factories, oil fields, and chemical plants were humming with orders for war materiel for Great Britain; the U.S. armed services were ordering pool tables for the new training camps being established all over the country, and the Depression was gone. Harold and Len enjoyed working together. It was a busy, fun time for both young men, until Harold was drafted into the Army Air Force in August, 1942. Brother Art then came down and ran the dealership until he had to close shop when he was drafted into the Army in November. Len, who had a polio-withered leg, was draft-exempt and returned to St. Louis.

The War Years, starting in December, 1941 and ending in September, 1945 changed the lives and activities of all Americans. Eventually, almost every single, healthy young man was either in the Armed Services, wartime industries, or employment that was war-related and draft exempt. Ed, Ernie, Dolph and their older employees adapted to the changed conditions. The repairing of tables, cues and balls continued — even grew — as new equipment and parts were no longer available. Table construction ground to a halt as steel for table frames, screws, bolts, and pocket irons couldn’t be purchased. Small pool rooms and bars closed when their owners went to war or wartime employment. Many sold their pool tables to A E. Schmidt Co., and most of the tables went into company storage. With almost a century of experience, the family knew how to cope with wars and tough times.

When the War ended, Harold, Art, and most of the other Company draftees returned to resume their careers at AESCO. Ten million young men were discharged from the Armed Services and came home to re-build their lives. Many returned to their former jobs, and 7 million took advantage of the G.I. Bill of Rights — the popular name for the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 which:

- Paid weekly unemployment benefits for as long as a year to those who were unable to find jobs.

- Paid monthly living allowance and tuition for veterans attending schools or college.

- Permitted the Federal Government to guarantee small loans to veterans to help them start in business, build homes, or buy farms.

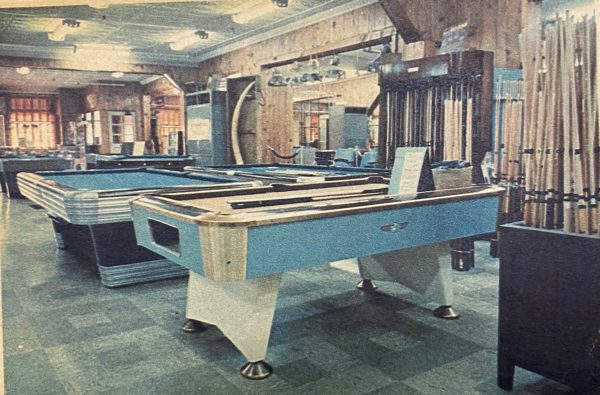

For several years Billiards boomed. According to IRS records, by 1948 there were 55,000 businesses purchasing $20 per table “Special Tax Stamps” (This “war” tax was imposed in 1940 and not lifted until 1965.) Once again, the Company could sell more tables than it could make. The Wendt Company in Milwaukee, which had been the sole source of tables for many small dealers, had closed its factory during the War, and when it re-opened in 1945 it had no trained work force and could not supply enough tables to satisfy Schmidt’s needs. A decision was made to buy or build a facility where all operations — office, sales, and warehouse could be in one work location.

Early in 1946 a very old, substantially constructed building at First and Sidney Streets was put on the market. In addition to having enough space to satisfy the Company’s needs, it had the convenience of a railroad siding from which slate could be moved from boxcars directly to the Company’s dock. The price was right.

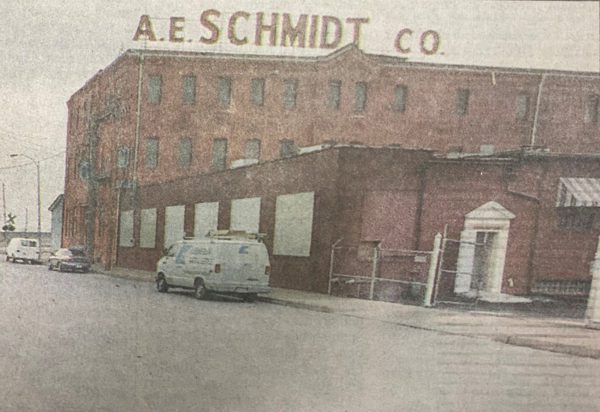

When Ed and Ernie took their Dad to look at their find. Oscar exclaimed “Why that’s the table factory where I worked in the ’80’s!!” AESKO Realty purchased the building in May, 1946, and after major repairs AESCO moved all of its operations to 112 Sidney Street. If walls could only talk!!

Adolph Kliefoth retired in 1945, his Company stock was sold to the other AESCO shareholders, and his partnership interest in AESKO Realty was purchased by Ernie and Ed’s wives, Ruth and Hilda.

Oscar Schmidt had come to work almost every day for 75 years. At the end of his last work day, November 11, 1950, be was stricken by a ruptured ulcer. That evening, when Ernie and Harold visited him at the hospital, he told them “Well, they finally got me into one of these places. Anyway, I’m happy to have seen the Company reach its 100th Anniversary”. He expired early the next morning. The family mourned his passing but celebrated the life of this quiet, no-nonsense man who had overcome every adverse condition in his personal and business experience, and set an example for his descendants.

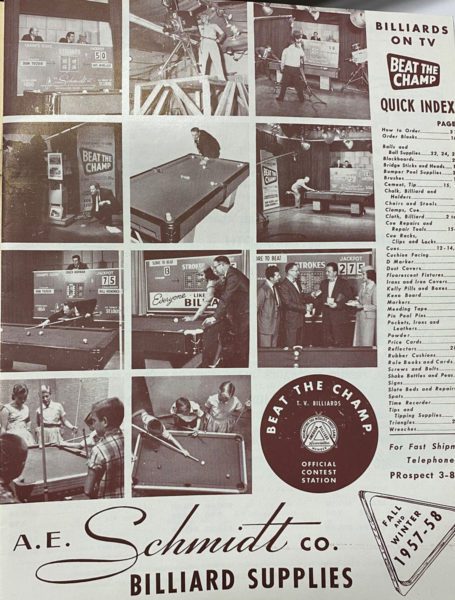

By 1950 the end-of-war boom was busted. A new competitor — TELEVISION — fascinated Americans and moved the players home to enjoy shows and sports events with their families. Some billiard room proprietors installed large screen TV’s, but the pictures stopped billiard action as the players sat down to watch the shows. Two-thirds of the billiard rooms operating in 1950 were defunct by 1960.

“Bumper Pool”, a game played in German bars by soldiers of the U.S. Occupational force was introduced to America in 1956. Within 2 years, 250,000 tables had been built by the Coin-operated Amusement Game industry. Following that success, millions of 3-1/2×7 foot, small size coin-operated 6-pocket pool tables — almost all constructed by the Amusement companies — were installed in taverns all over the country. Apparently nothing could stop the popularity of the game, but where it would be played was changing. For starters, most of the better billiard room players moved from the rooms to the bars — where the “action” was.

Billiards experienced a welcome boost in 1961. “The Hustler”, a motion picture starring Paul Newman and Jackie Gleason as sharks preying on suckers in pool rooms, was a box office success, and, instead of sinking the game further into its perceived sludge had the opposite effect of stirring players to return to playing on the large tables.

Despite this momentary up-surge, pool rooms were still closing down in droves and by 1965 directories listed only 3,500 rooms nation-wide.

After experiencing numerous ups and downs in the Billiard business over the past century, the Schmidt family had no doubt that the basic appeal of the game itself — now almost 500 years old — would continue its attraction for young and old boys and (hopefully) girls.

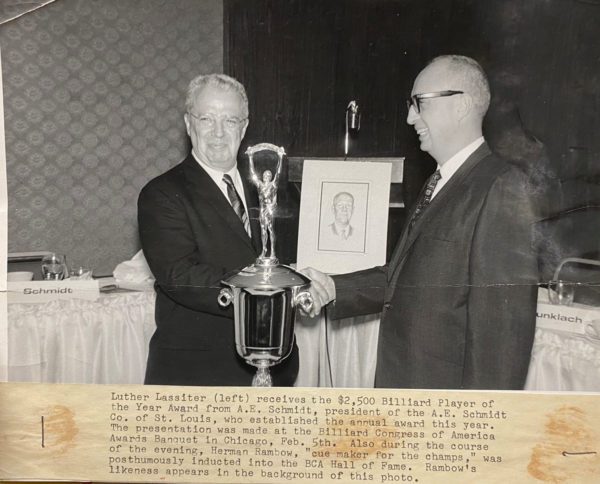

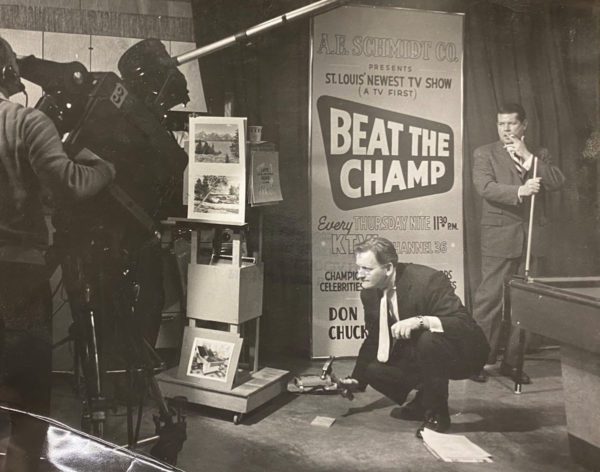

The Billiard Congress of America (BCA), organized in 1948, was producing an Official Rule Book and sponsoring National Championship Tournaments; but there was virtually no communication between manufacturers, billiard room proprietors, or players. A.E. Schmidt Co., in January, 1961 moved into this communication void with a monthly newsletter CHALK UP, which it sent to its national mailing list. The timing was right — in June of ’61 the Hustler movie was released, and in October a series of “Hustler” tournaments was launched by George and Paulie Jansco in Johnston City, Illinois.

Damon Runyon would have loved the “characters” playing in these tournaments: Minnesota Fats, Squirrel, Wimpy, Bear, Weenie-Beanie, Cornbread Red, Ugly Utley, Daddy Warbucks, Cowboy Jimmy and other colorful guys played “One-Pocket” for the $5,000 prize money. Nine-Ball, straight 14.l Pockets, and One-Pocket were played in 1962 and 1963 for $10,000 in prizes, and these tourneys attracted writers from newspapers and magazines. In 1964 the prize money grew to $20,000. By 1965 George and Paulie were master-minding the Stardust Open at Las Vegas with a $30,000 purse and the nine-ball games were being televised and reaching a national audience.

The BCA, most of the top 3-cushion and 14.1 players, and many manufacturers deplored the “Hustler” image that was being projected — BUT — it was the “only game in town”. The resulting publicity spawned smaller tournaments nation-wide, and prompted the BCA to host, in 1966, the First Annual U.S. Open Pocket Billiard Tournament and Trade Show (with 10 exhibitors) at the Sherman House Hotel in Chicago. The Second Annual Open was hosted by A.E. Schmidt Co. at the Jefferson Hotel in St. Louis.

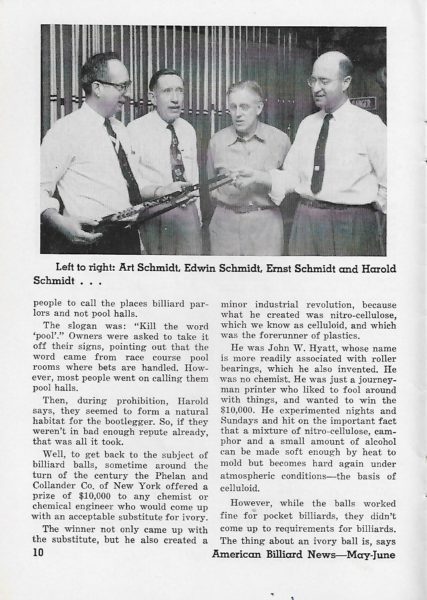

During these eventful years, management changes were occurring at the Company. Ed Schmidt relinquished the Presidency to Art in 1952, but continued as Chairman of the Board. In 1968 Harold “retired”, but continued to operate the Schmidt dealerships he owned in Little Rock, Dallas, Dayton, Ohio, and Springfield, Illinois. In 1972, A.E. Schmidt opened a branch store at 6528 Clayton Road in St. Louis and the following year this store was purchased and operated by Harold and Art.

The demise of the old time “Pool rooms” marked the end of another chapter in the history of Billiards. Old rooms may have died, but their old tables hadn’t — they simply moved into family “rec rooms” — dens, garage basements, un-used dining rooms, attics or work shop areas.

But, the 4 l/2’x 9′ and over-size 4’x8′ pool room tables were too large to fit in available spaces in a majority of homes. A few table manufactures started producing 3 1/2’x7′ bar size and 4’x8′ home size tables to fill this void.

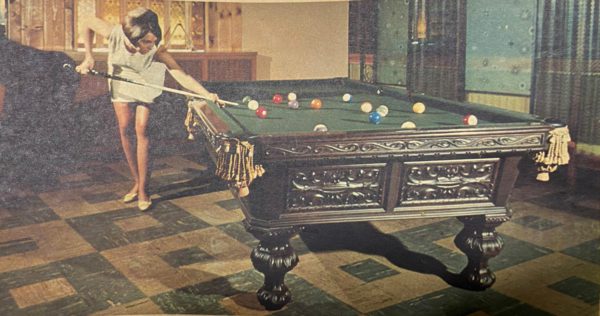

Many times the “lady of the home” dis-liked the passe formica and chrome-plated “art deco” style of pool room equipment, so, the manufacturers searched through century-old pictures and began producing “faux antique” styles that the ladies loved.

Suddenly, it seemed, there weren’t enough tables of all sizes and designs being manufactured to meet the demand. By 1970, there were nearly 100 firms and individuals making light weight non-slate or slate bed tables, compared to the fewer than 20 old line manufacturers existent in 1960.

Brunswick made some changes. The company started producing 7′ and 8′ tables with light weight vinyl finish plywood frames and 3/4″ slate or 2″ thick “honeycomb” cement board beds.

New administrators in the Billiard Division scrapped the policy of selling retail: henceforth billiard products would be sold through Brunswick Franchised Dealers.

AESCO, meanwhile, had decided that it wanted to maintain the company’s reputation for building heavy duty long-lasting equipment, therefore it would make only slate bed tables. After a few had been made with 3/4″ slate, the policy was changed to use only l” thick slate on all Schmidt tables and to buy and sell other manufacturers’ light weight products. In 1973, A.E. Schmidt Co. became a Brunswick Franchised Dealer and could offer customers the best in light weight tables along with all of the heavier Brunswick models, including the popular Gold Crown professional line.

Ed Schmidt and most of his business buddies who had worked so hard to form the Billiard and Bowling Institute of America and the Billiard Congress of America weren’t around to see the fulfillment of their dreams. Ed died in 1972.

Under his leadership, A.E. Schmidt Co. had advanced from a local to a national player in the billiard supply field. In the 1960’s when billiard table production had become a minor part of Brunswick’s conglomerate business, that company was debating whether or not to continue billiard table construction. In order to judge the potential market a questionnaire was mailed to almost every billiard room still operating in the United States. One of the questions asked was “what is the manufacturer’s name on your table or tables name-plates?” The actual numbers on the survey replies were never published, but through the grapevine it was learned that Brunswick plates were on a majority of tables. A.E. Schmidt plates were in second place.

Brunswick then decided to continue its Billiards Division. That decision was a “plus” for the industry.

There was no question of AESCO’s decision: the Arther E. Schmidt family would continue the management and eventual ownership of the A.E. Schmidt Company. Art and Florence Schmidt had four children: two daughters — Patti born in 1948 and Robyn in 1963, and two sons — Tom born in 1952 and Kurt in 1959. Following family tradition, the children worked at AESCO part time during their school years; and eventually every family member filled a responsible position in the corporation.

In 1977, Art and Tom formed a corporation to open Schmidt Billiard Supplies, Inc. at Springfiield, MO. It wasn’t the best of times for the billiard industry. As the HISTORY OF THE BCA tells it “The 80’s were a transitional decade for pool. The condition of the game started off horribly, then got steadily worse until 1986, when the film version of “The Color of Money” appeared. Within a year the renaissance had begun, with even greater strength than the revival caused by “The Hustler” 25 years earlier”. The Renaissance didn’t start soon enough for Tom, he closed the Springfield store in early 1987.

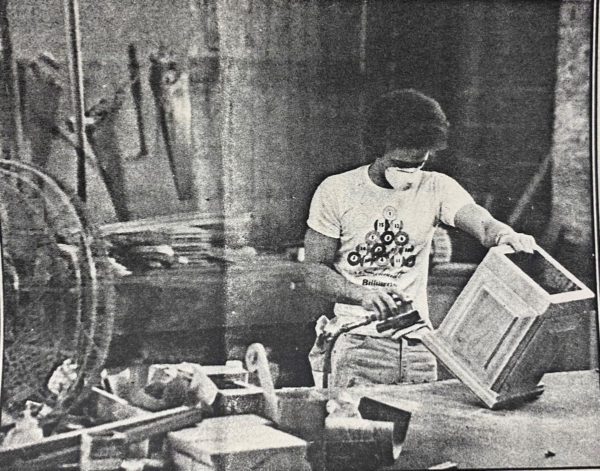

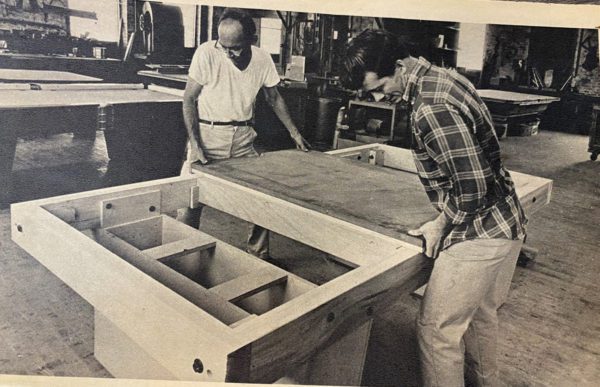

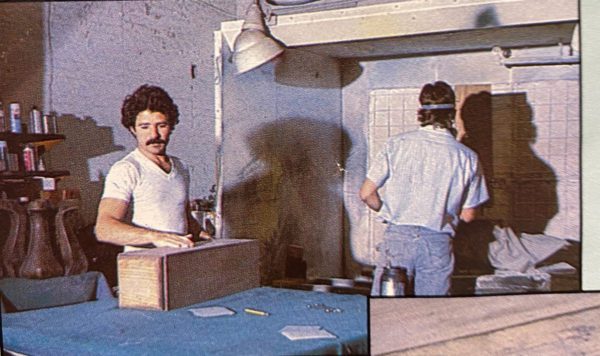

Also in 1977, Kurt started working full time at AESCO. “Working” is probably the wrong word to describe his relationship with billiards — actually it has been a beautiful love affair. He loved every facet of the business — Administration, Production, and Marketing. Like his predecessors — Ernst, Oscar, and Ernie — Kurt particularly loved to work with wood, using his hands and mind to design, shape and repair tables. “Full time” was the correct term for his business courtship; all too frequently, after kissing his wife and children good night, he would return to the factory and work past midnight on a special project; he seemed to have an endless source of energy — at 8 A.M. he’d be back on the job, fresh as a daisy.

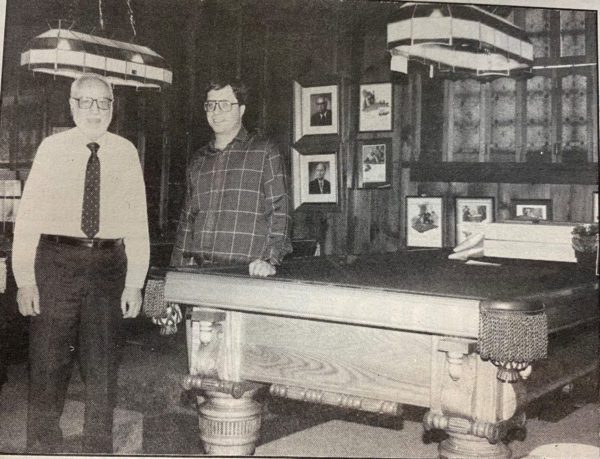

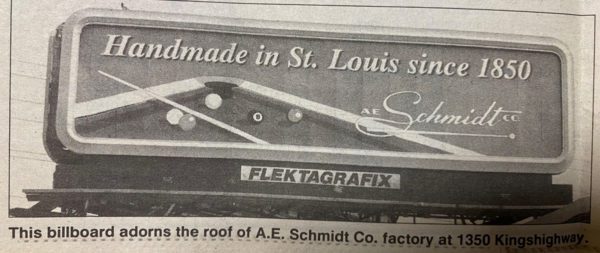

To the family, Kurt was a Renaissance Man for its business. In 1993 he opened a branch store in St. Louis’ West County, and in 1997 a branch in South County. In March, 1995 he moved the factory and repair shop to several large buildings at 1350 South Kingshighway and tripled table production. Retail sales were continued at 112 Sidney Street until mid-1998 when the 180 year old building was sold to Wayne and Joan Long. The Longs have a flourishing restaurant, banquet, and catering business nearby — THE 9TH STREET ABBEY — so named because it occupied an old church clerical residence. Wayne and Joan retro-fitted the 55,000 sq. ft. Schmidt building for their banquet and catering operations; bought antique pool tables and artifacts from Kurt for the new lounge area; obtained his permission to leave the enormous A.E. Schmidt Co. sign on the roof so that the character of the building would keep touch with its past, and named this facility THE FACTORY.

At this time, July 2000, this story is a “work in progress” and the recording of the activities of the Fifth and Following Generations will be left to present and future descendants of Ernst, Oscar, Edwin, Ernest, Arthur and Harold Schmidt.

Harold’s sons — Bob, born in 1948 and Fred in 1953 are active in the Billiard Industry; not as employees or stockholders of A.E. Schmidt Co., but as Schmidt table distributors:

- Bob at Jones Bros. Distributing Co. in Little Rock, Arkansas: Jones Bros Website

- Fred at Schmidt Billiards and Game Rooms in Columbia, Missouri: Schmidt Billiards Website

6th Generation

Michael, Stephanie & Rachel Schmidt

Just like the 4th and 5th generation, the 6th generation has been working at the company doing small jobs here and there since they were young.

Currently, the 6th generation is helping increase the wholesale production of the 5th generation and bringing the company into the digital age. Each of Kurt and Karen’s children have their own passions and strengths within the company. Michael oversees the factory and makes sure production goes smoothly, Stephanie excels at selling and handles most of our wholesale operations, and Rachel is passionate about designing tables and the behind-the-scenes analytical work.

Acknowledgement

The Fourth Generation Schmidt Family knew little of Ernst Schmidt’s “roots” before Elizabeth Schmiemeier Schmidt — Dr. Edwin H. Schmidt, Jr’s. wife — became interested in the Schmiemeier and Schmidt family histories.

“Schmie” spent countless hours in Missouri, Illinois, and Germany poring over records of births, marriages, divorces, and deaths written in English, German, and French that she found in Geneological Society, Church, County Seat, and cemetery records, and in a cash journal and personal letters to Ernst which he had retained.

She copied as many as she could of the written records of the Schmidt-Grimminger-Zelch, Kliefoth-Berblinger family connections. Her research of our “roots” help us to see how our family tree grew.

Elizabeth, we are all indebted to you!